In 1997, University of Oregon professor Paul Slovic sat at his desk in Oregon, but his mind was 8,000 miles away in Rwanda.

It was just three years after the Rwandan genocide that left an estimated 500,000–1,000,000 Rwandans dead during a 100-day period.

President Bill Clinton and his administration were widely criticized for failing to act. Despite receiving intelligence about the "final solution to eliminate all Tutsis,” It took over a month since the beginning of the massacre for Clinton to publicly use the word genocide.

Clinton later apologized for his administration’s failure to intervene. "It may seem strange to you here,” he said in a visit to the Rwandan capital, Kigali, “but all over the world there were people like me sitting in offices, day after day after day, who did not fully appreciate the depth and speed with which you were being engulfed by this unimaginable terror."

Back at his desk, Slovic started thinking: why were we sometimes insensitive to the value of human life? His research would culminate in what would famously become known as “The Collapse of Compassion,” with some of the major points highlighted below.

Psychosocial barriers to empathy

Slovic started with Weber’s law, a phenomenon that has been a popular framework for understanding human perception since the 19th century.

It says that the more intense something is, the harder it is to notice a change, but if the intensity is lower, it’s easier to notice the change. And if there is more of something, then more change is needed to pass your difference threshold, whereas the less there is of something, then less change is needed to pass your difference threshold. For example, losing five dollars on the street might not phase us. But if those five dollars count as 50% of all the money to our name, we’ll definitely be upset. In other words, the amount stays the same ($5), but the proportion changes, and so does our perceptual difference.

Slovic wondered if maybe these same limits applied to our perception of people. Do we have limits to how much empathy we can feel for people? And does our ability to care about people decrease as the number of people to care about increases?

Maybe, Slovic reasoned, this explained why we failed to take action in Rwanda. So he started digging further.

The limits of empathy

Weber's law was just one part of Slovic's collapse of compassion — the other part was a study that gave Swedish university students the opportunity to donate to Save the Children. The university students were split into three groups:

Group 1 received Rokia’s story and photo.

Group 2 received Moussa’s story and photo with a similar description.

Group 3 received both Rokia’s and Moussa’s stories and were told that any donation would go to both Rokia and Moussa.

The stories looked something like this:

Rokia, a seven-year-old girl from Mali, Africa, is desperately poor and faces a threat of severe hunger or even starvation. Her life will be changed for the better as a result of your financial gift. With your support, Save the Children will work with Rokia's family and other members of the community to help feed her, provide her with education, as well as basic medical care and hygiene education.

On their own, Rokia and Moussa received roughly the same amount of donations. But when their stories were told together, they received 20% fewer donations. The students also reported feeling less empathy for both Rokia and Moussa.

In other words, not only was our capacity limited when it came to distinguishing differences, but it was limited when it came to empathizing with others too. As the number of people increased, our ability to feel for these individuals decreased. And our ability to empathize with others didn’t just fall off in large groups of people — we started feeling less empathy for others starting at just two people.

In other words, you’re not a bad person — you just can’t focus on more than one person at a time. Slovic called this “the collapse of compassion.”

Hacking the limits of empathy in a new age

Slovic called these findings “unsettling,” writing in 2007 that our capacity to feel is biologically and psychologically limited. He worried that this inability to feel empathy for more than one person at a time would mean that as humans, we would always err on the side of apathy or inaction during major crises. In other words, in global tragedies or disasters, we cannot depend on the innate morality of good people.

But a lot has changed since then. When Slovic published his paper in 2007, 120 million people were online. Today, that number is closer to 4 billion.

In this new age, statistics about people affected by genocide, war, catastrophes, and health issues have new meaning — the internet has given us the opportunity to put a face and name to each of those people and broadcast them around the world.

In November 2010, New York City photographer Brandon Stanton started Humans of New York (HONY), a popular photo blog that profiles individuals on the street of New York. Recently, Stanton expanded his blog to profile the stories of refugees across Europe and the Middle East, in partnership with the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHCR).

Major organizations like the UNHCR are increasingly asking storytellers like Stanton to broadcast individual human stories on the internet. By bringing individual human stories to major crises, Stanton and the UNHCR are working to effectively scale empathy for an issue that may be too remote or unfamiliar for some to understand — starting with Stanton’s 17.5 million Facebook followers.

"These migrants are part of one of the largest population movements in modern history,” wrote Stanton on HONY’s Facebook page, “but their stories are composed of unique and singular tragedies."

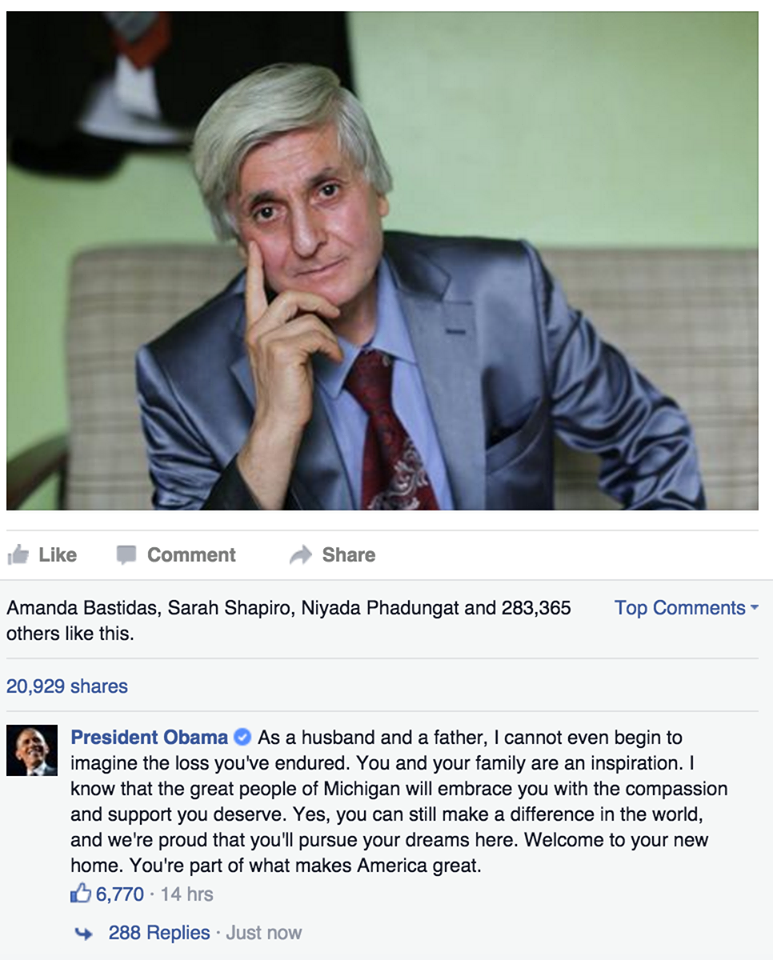

One of the portraits of a Kurdish civil engineer went viral. In just seven photos detailing the life of “The Scientist,” Stanton brought the refugee crisis into focus.

The response to the scientist’s story was enormous. President Obama welcomed him to the US in a public Facebook comment, a comment that made headlines and drove international attention to the refugee crisis. Less than two weeks later, Stanton launched an online fundraiser to support the 11 refugee families he had profiled that month. In just 48 hours, 18,000 people donated over $750,000 to his campaign.

Stanton’s project has helped American audiences better understand the human costs of the Syrian crisis — one photograph at a time.

Each portrait has succeeded where news reports detailing the 4 million who have fled Syria have failed — they have confirmed the scope of the tragedy while making each person’s life real, intimate, and human.

With "the collapse of compassion," Slovic helped demonstrate that we’re hard-wired against caring for large groups of people, but the internet is changing the way we interact with the world. It’s enabled us to find and share individual stories in the furthest reaches of the globe. The internet, perhaps more than any tool that has preceded it, might be the answer to Slovic’s collapse of compassion. It might just be the key to helping us feel something for someone else.

Michelle Fernández

Telling the stories of Watsi patients and donors. Head of Content at Watsi.